Clusters of Athletes

At some time, most athletes experience periods of underperformance. What are the potential causes and contributing factors?

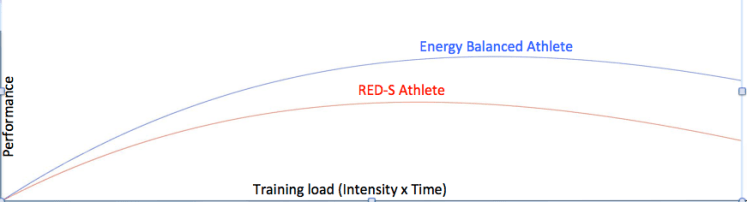

Effective training improves sports performance through a process of adaptation that occurs, at both the cellular and system levels, during the recovery phase. Training overload must be balanced with sufficient subsequent recovery. A long-term improvement in form is expected, following a temporary dip in performance, due to short-term fatigue.

However, when an athlete experiences a stagnation of performance, what are the potential underlying causes? How should these be addressed to prevent an acute situation developing into a more chronic spiral of decreasing performance?

Depending on clinical presentation, the first step is to exclude medical conditions. Potential infective causes include Epstein Barr virus (particularly in young athletes), Lyme disease and Weil’s disease. Systemic inflammatory conditions should be considered. Endocrine and metabolic causes include pituitary, gonadal, adrenal, thyroid dysfunction, blood sugar control, and malabsorption.

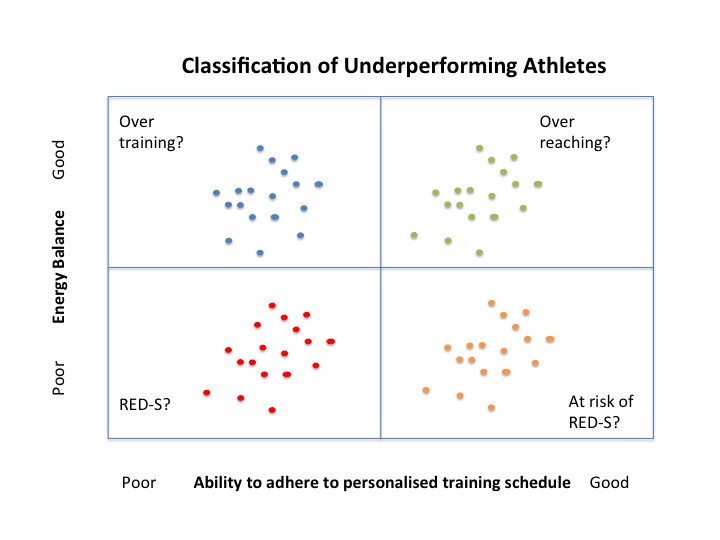

If medical conditions are excluded, attention should turn to the athlete’s energy balance in the context of adherence to the current training plan. Potential causes of underperformance, the inability to improve in training and competition, are illustrated in the diagram above.

Athletes in the upper right quadrant fail to live up to performance expectations, in spite of maintaining a good energy balance while adhering to the prescribed training plan. However, they may represent non-functional overreaching, where overload is not balanced with sufficient recovery. In other words, the periodisation of training and recovery is not optimised. The balance between chronic training load (fitness) and acute training load (fatigue) provides a useful metric for assessing form. Heart rate variability (HRV) can be another potentially useful measure in detecting aerobic, endurance fatigue. If the training plan is not producing the expected improvements, then this plan needs revising. Don’t forget that sleep is essential to facilitate endocrine driven adaptations to exercise training.

Athletes in the lower right quadrant are of more concern. Inadequate energy balance, especially during periods of increased training load or intentional weight loss, can be a cause of underperformance, despite the athlete being able to adhere to the training plan. This would correspond to being at risk of developing relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) on the amber warning in the risk stratification laid out by the International Olympic Committee.

Both of these groups are able to adhere to a training plan, but suboptimal training and recovery periodisation and/or insufficient energy intake can produce a situation of underperformance. Intervention is required to prevent them moving into the clusters on the left, representing a more chronic underperformance scenarios that are therefore more difficult to rectify.

Athletes in the upper left quadrant exhibit overtraining syndrome: a prolonged maladaptation process accompanied by a decrease in performance (not merely stagnation) and inability to adhere to training plan. The metric of decreased HRV and inability of heart rate to accelerate in response to exercise have been suggested as markers of overtraining.

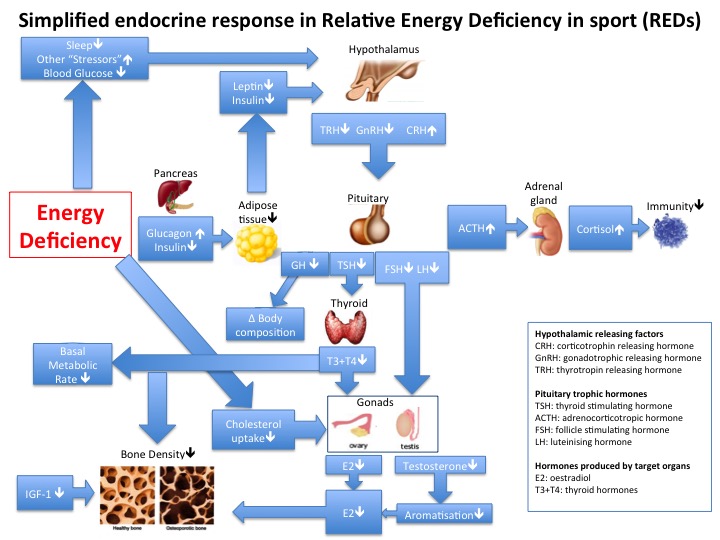

Those athletes in the lower left quadrant fall into the RED-S category, where multiple interacting Endocrine networks are impacted by an energy deficient state. RED-S not only impairs sports performance, but impacts both current and future health. For example low endogenous levels of sex steroids and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) disrupt formation of bone microarchitecture and bone mineralisation, resulting in increased risk of recurrent stress fracture in addition to potentially irreversible bone loss in the longer term. In cases of recurrent injury and underperformance amongst athletes it is imperative to exclude Endocrine dysfunction and then consider whether RED-S is the fundamental cause.

There are many potential causes of underperformance in athletes. Once medical conditions have been excluded, the main aim should be to prevent acute situations becoming chronic and therefore more difficult to resolve.

For further discussion on Endocrine and Metabolic aspects of SEM come to the BASEM annual conference 22/3/18: Health, Hormones and Human Performance

References

Sport Endocrinology Dr N. Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine 2017

Sport Performance and RED-S, insights from recent Annual Sport and Exercise Medicine and Innovations in Sport and Exercise Nutrition Conferences Dr N.Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine 2017

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport CPD module for British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine

Optimal Health: For All Athletes! Part 4 – Mechanisms, Dr N. Keay, British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine

Balance of recovery and adaptation for sports performance Dr N. Keay, British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine

Sleep for health and sports performance Dr N. Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine

Optimal health: including female athletes! Part 1 Bones Dr N.Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine

Inflammation: why and how much? Dr N. Keay, British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine

Fatigue, Sport Performance and Hormones… Dr N.Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine

Part 3: Training Stress Balance—So What? Joe Friel

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Science for Sport

Relative Energy Deficiency in sport (REDs) Lecture by Professor Jorum Sundgot-Borgen, IOC working group on female athlete triad and IOC working group on body composition, health and performance. BAEM Spring Conference 2015.

Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Overtraining Syndrome: Joint Consensus Statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of

Sports Medicine. Joint Consensus Statement. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2012

The Holy Grail of any training program is to improve performance and achieve goals.

The Holy Grail of any training program is to improve performance and achieve goals.