Athletic Fatigue: Part 1

Interpreting athletic fatigue is not easy. Consideration has to be given to context and time scale. What are the markers and metrics that can help identify where an athlete lies in the optimal balance between training, recovery and nutrition which support beneficial adaptations to exercise whilst avoiding the pitfalls of fatigue and maladaptation? This blog will discuss the mechanisms of athletic fatigue in the short term.

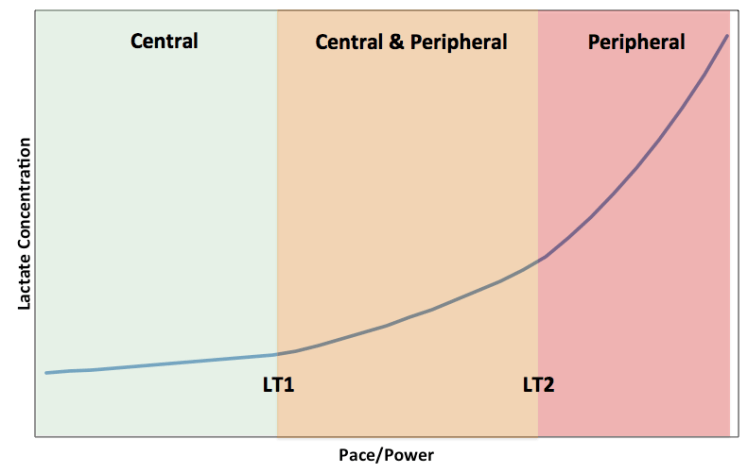

In the short term, during an endurance training session or race, the temporal sequence of athletic fatigue depends on duration and intensity. It is proposed that below lactate threshold (LT1), a central mechanism governs: increasing central motor drive is required to maintain skeletal muscular power output until neuromuscular fatigue cannot be overcome. From lactate threshold (LT1) to lactate turn point (LT2), a combination of central and peripheral factors (such as glycogen depletion) are thought to underpin fatigue. During high intensity efforts, above LT2 (which correspond to efforts at critical power), accumulation of peripheral metabolites and inability to restore homeostasis predominate in causing fatigue and ultimately inability to continue, leading to “task failure”. Of course there is a continuum and interaction of the mechanisms determining this power-duration relationship. As glycogen stores deplete this impacts muscle contractility by impairing release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle. Accumulation of metabolites could stimulate inhibitory afferent feedback to central motor drive for muscle contraction, combined with decrease in blood glucose impacting central nervous system (CNS) function.

Even if you are a keen athlete, it may not be possible to perform a lactate tolerance or VO2 max test under lab conditions. However a range of metrics, such as heart rate and power output, can be readily collected using personalised monitoring devices and then analysed. These metrics are related to physiological markers. For example heart rate and power output are surrogate markers of plasma lactate concentration and thus can be used to determine training zones.

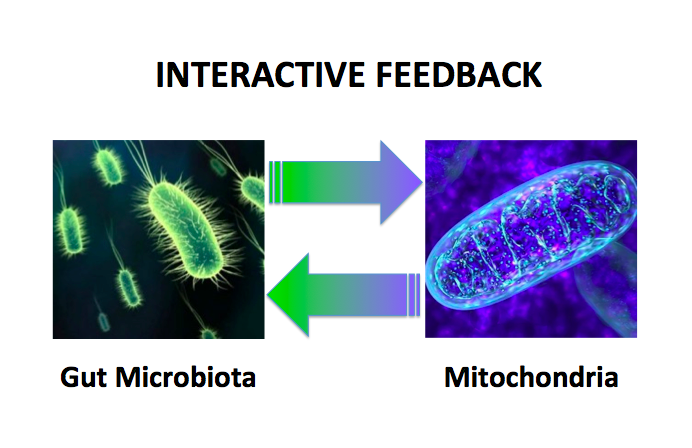

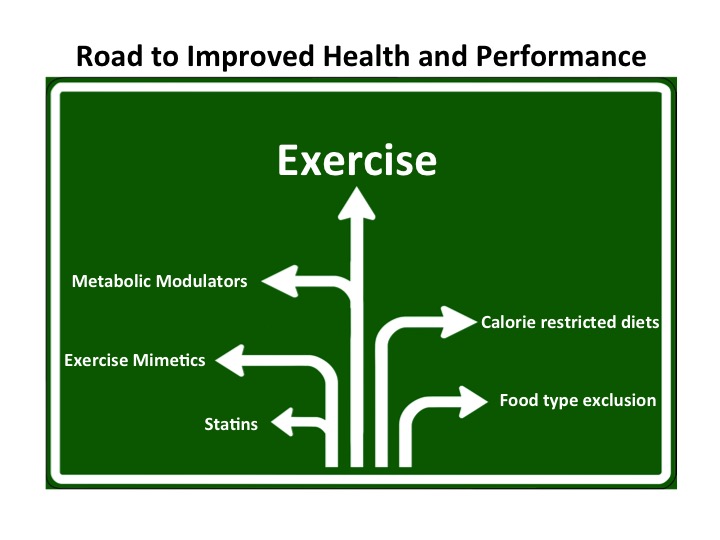

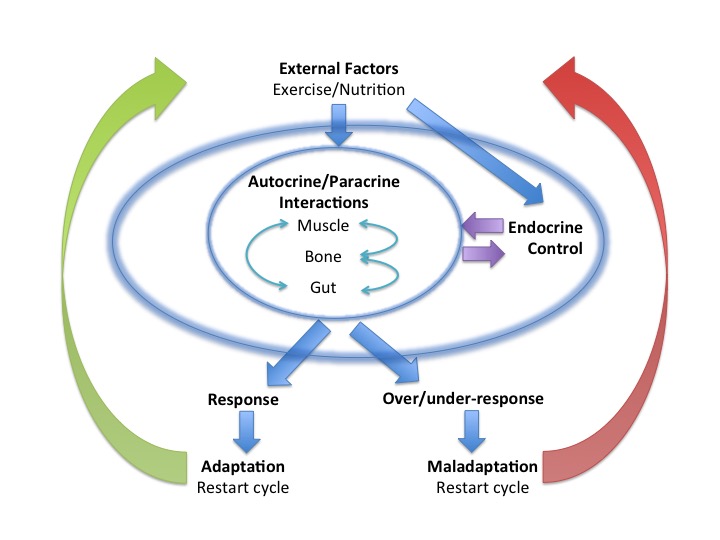

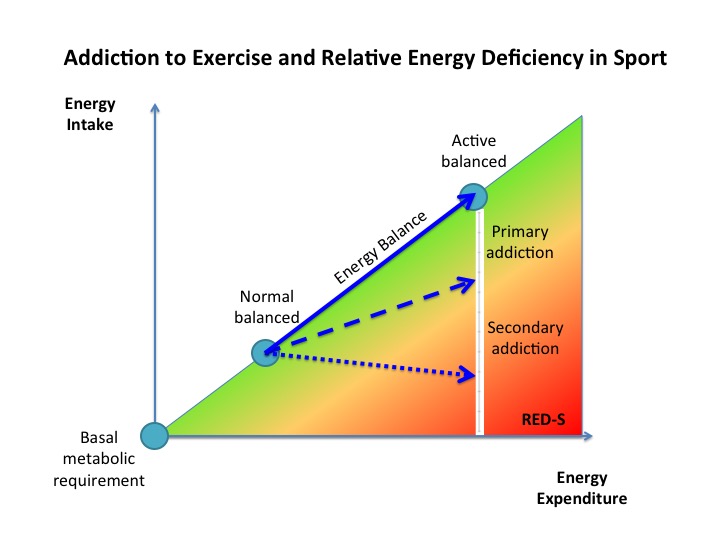

A training session needs to provoke a degree of training stress, reflected by some short term fatigue, to set in motion adaptations to exercise. At a cellular level this includes oxidative stress and exerkines released by exercising tissues, backed up by Endocrine responses that continue to take effect after completing training during recovery and sleep. Repeated bouts of exercise training, followed by adequate recovery, result in a stepwise increase in fitness. Adequate periodised nutrition to match variations in demand from training also need to be factored in to prevent the Endocrine system dysfunction seen in Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S), which impairs Endocrine response to training and sports performance. Integrated periodisation of training/recovery/nutrition is essential to support beneficial multi-system adaptations to exercise on a day to day time scale, over successive training blocks and encompassing the whole training and competition season. Psychological aspects cannot be underestimated. At what point does motivation become obsession?

In Part 2 the causes of athletic fatigue over a longer time scale will be discussed, from training blocks to encompassing whole season.

References

Endocrine system: balance and interplay in response to exercise training

Power–duration relationship: Physiology, fatigue, and the limits of human performance European Journal of Sport Science 2016

Strava Ride Statistics Science4Performance 2017

Sleep for health and sports performance Dr N Keay, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S) Practical Considerations for Endurance Athletes

Sports Endocrinology – what does it have to do with performance? Dr N Keay, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017

Optimal Health: For All Athletes! Part 4 – Mechanisms Dr N Keay, British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine 2017

Addiction to Exercise – what distinguishes a healthy level of commitment from exercise addiction? Dr N Keay, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017