Sport Performance and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport

The Holy Grail of any training program is to improve performance and achieve goals.

The Holy Grail of any training program is to improve performance and achieve goals.

Periodisation of training is essential in order to maximise beneficial adaptations for improved performance. Physiological adaptations occur after exercise during the rest period, with repeated exercise/rest cycles leading to “super adaptation”. Adaptations occur at the system level, for example cardiovascular system, and at the cellular level in mitochondria. An increase in mitochondria biogenesis in skeletal muscle occurs in response to exercise training, as described by Dr Andrew Philip at a recent conference at the Royal Society of Medicine (RSM). This cellular level adaptation translates to improved performance with a right shift of the lactate tolerance curve.

The degree of this response is probably genetically determined, though further research would be required to establish causal links, bearing in mind the ethical considerations laid out in the recent position statement from the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) on genetic testing in sport. Dr David Hughes, Chief Medical Officer of the AIS, explored this ethical stance at a fascinating seminar in London. Genetic testing in sport may be a potentially useful tool for supporting athletes, for example to predict risk of tendon injury or response to exercise and therefore guide training. However, genetic testing should not be used to exclude or include athletes in talent programmes. Although there are polymorphisms associated with currently successful endurance and power athletes, these do not have predictive power. There are many other aspects associated with becoming a successful athlete such as psychology. There is no place for gene doping to improve performance as this is both unethical and unsafe.

To facilitate adaptation, exercise should be combined with periodised rest and nutrition appropriate for the type of sport, as described by Dr Kevin Currell at the conference on “Innovations in sport and exercise nutrition”. Marginal gains have a cumulative effect. However, as discussed by Professor Asker Jeukendrup, performance is more than physiology. Any recommendations to improve performance should be given in context of the situation and the individual. In my opinion women are often underrepresented in studies on athletes and therefore further research is needed in order to be in a position to recommend personalised plans that take into account both gender and individual variability. As suggested by Dr Courtney Kipps at the Sport and Exercise Conference (SEM) in London, generic recommendations to amateur athletes, whether male or female, taking part in marathons could contribute to women being at risk of developing exercise associated hyponatraemia.

For innovation in sport to occur, complex problems approached with an open mind are more likely to facilitate improvement as described by Dr Scott Drawer at the RSM. Nevertheless, there tends to be a diffusion from the innovators and early adapters through to the laggards.

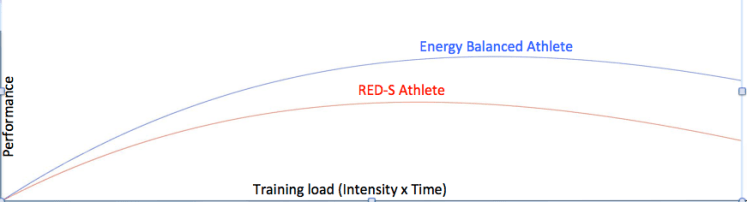

Along the path to attaining the Holy Grail of improved performance there are potential stumbling blocks. For example, overreaching in the short term and overtraining in the longer term can result in underperformance. The underlying issue is a mismatch between periodisation of training and recovery resulting in maladapataion. This situation is magnified in the case of athletes with relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Due to a mismatch of energy intake and expenditure, any attempt at increase in training load will not produce the expected adaptations and improvement in performance. Nutritional supplements will not fix the underlying problem. Nor will treatments for recurrent injuries. As described by Dr Roger Wolman at the London SEM conference, short term bisphosphonante treatment can improve healing in selected athletes with stress fractures or bone marrow lesions. However if the underlying cause of drop in performance or recurrent injury is RED-S, then tackling the fundamental cause is the only long term solution for both health and sport performance.

Network effects of interactions lead to sport underperformance. Amongst underperforming athletes there will be clusters of athletes displaying certain behaviours and symptoms, which will be discussed in more detail in my next blog. In the case of RED-S as the underlying cause for underperformance, the most effective way to address this multi-system issue is to raise awareness to the potential risk factors in order to support athletes in attaining their full potential.

For further discussion on Endocrine and Metabolic aspects of SEM come to the BASEM annual conference 22/3/18: Health, Hormones and Human Performance

References

Teaching module RED-S British Association Sport and Exercise Medicine

From population based norms to personalised medicine: Health, Fitness, Sports Performance Dr N. Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine 22/2/17

Balance of recovery and adaptation for sports performance Dr N. Keay, British Association Sport and Exercise Medicine 21/1/17

Sleep for health and sports performance Dr N. Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine 7/7/17

Fatigue, Sport Performance and Hormones… Dr N. Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine

Annual Sport and Exercise Medicine Conference, London 8/3/17

Bisphosphonates in the athlete. Dr Roger Wolman, Consultant in Rheumatology and Sport and Exercise Medicine, Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital

Collapse during endurance training. Dr Courtney Kipps, Consultant in Sport and Exercise Medicine. Consultant to Institute of Sport, medical director of London and Blenheim Triathlons

Innovations in Sport and Exercise Nutrition. Royal Society of Medicine 7/3/17

Identifying the challenges: managing research and innovations programme. Dr Scott Drawer, Head of Performance, Sky Hub

Exercise and nutritional approaches to maximise mitochondrial adaptation to endurance exercise. Dr Andrew Philip, Senior Lecturer, University of Birmingham

Making technical nutrition data consumer friendly. Professor Asker Jeukendrup, Professor of Exercise Metabolism, Loughborough University

Innovation and elite athletes: what’s important to the applied sport nutritionists? Dr Kevin Currell, Director of Science and Technical Development, The English Institute of Sport

Genetic Testing and Research in Sport. Dr David Hughes, Chief Medical Officer Australian Institute of Sport. Seminar 10/3/17

Effects of adaptive responses to heat exposure on exercise performance

Over Training Syndrome, Ian Craig, Webinar Human Kinetics 8/3/17

The Fatigued Athlete BASEM Spring Conference 2014

Relative Energy Deficiency in sport (REDs) Lecture by Professor Jorum Sundgot-Borgen, IOC working group on female athlete triad and IOC working group on body composition, health and performance. BAEM Spring Conference 2015.

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, Meyer N, Sherman R, Steffen K, Budgett R, Ljungqvist A. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad-Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S).Br J Sports Med. 2014 Apr;48(7):491-7.