Health and Performance during Lifespan: latest research

Your lifespan depends on genetic and key lifestyle choices

Lifespan is dependent on a range of genetic factors combined with lifestyle choices. For example a recent study reported that an increase in one body mass index unit reduced lifespan by 7 months, whilst 1 year of education increased lifespan by 11 months. Physical activity was shown to be a particularly important lifestyle factor through its action on preventing age-related telomere shortening and thus reducing of cellular ageing by 9 years. Nevertheless, even though males and females have essentially identical genomes, genetic expression differs. This results in different disease susceptibilities and evolutionary selection pressures. More studies involving female participants are required!

Circadian clock

Much evidence is emerging about the importance of paying respect to our internal biological clocks when considering the timing of lifestyle factors such as eating, activity and sleep. For example intermittent fasting, especially during the night, and time restricted eating during the day enables metabolic flexibility. In other words, eating within a daylight time window will support favourable metabolism and body composition. No midnight snacks!

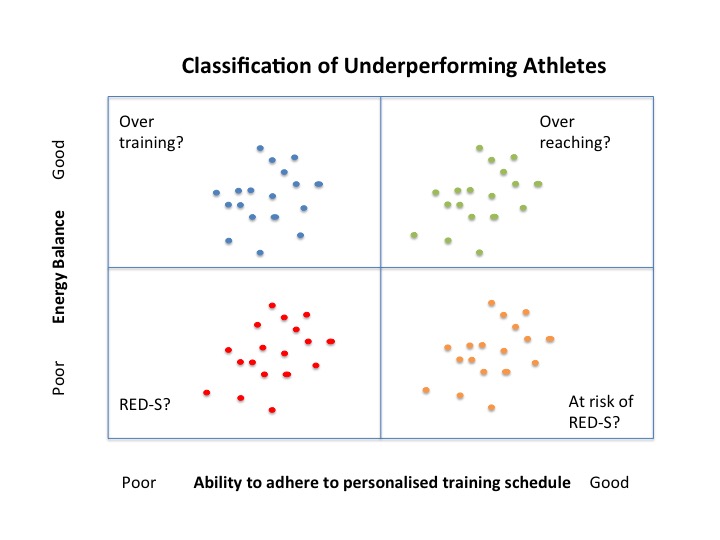

For athletes, even more care needs be given to timing of nutrition to support athletic performance. In the short term there is evidence that rapid refuelling after training with a combination of carbohydrate and protein favours a positive balance of bone turnover that supports bone health and prevents injury in the longer term. Periodised nutrition over a training season, integrated with exercise and recovery, is important in order to benefit from training adaptations and optimise athletic performance.

Protein intake in athletes and non athletes

Recovering from injury can be a frustrating time and some athletes may be tempted to reduce food intake to compensate for reduced training. However, recommendations are to maintain and even increase protein consumption to prevent a loss of lean mass and disruption of metabolic signalling. In the case of combined lifestyle interventions, such as nutrition and exercise aimed at reducing body weight, these should be directed at improving body composition. Adequate protein intake alongside exercise will maintain lean mass in order to minimise the risk of sarcopenia and associated bone loss which can occur during hypocaloric regimes. Good protein intake is important for bone health to support bone mineral density and reduce the risk of osteoporosis and fracture.

Adolescent Athlete

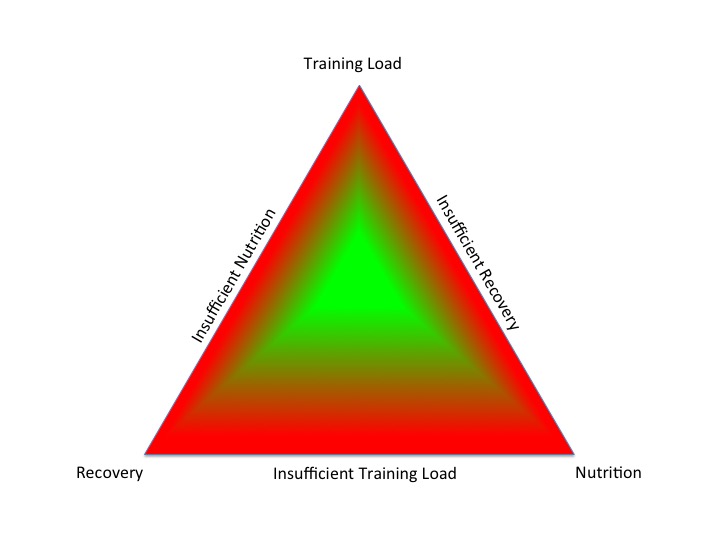

In the young athlete, integrated periodisation of training, nutrition and recovery is of particular importance, not only to support health and performance, but as an injury prevention strategy. Sufficient sleep and nutrition to match training demands are key.

Differences between circadian phenotype and performance in athletes

For everyone, whether athlete or reluctant exerciser, balancing and timing key lifestyle choices of exercise, nutrition and sleep are key for optimising health and performance. However there are individual differences when it comes to the best time for athletes to perform, according to circadian phenotype/chronotype. In other words personal biological clocks which run on biological time. An individual’s performance can vary by as much as 26% depending on the time of day relative to one’s entrained waking time.

Later in Life

Ageing can be can be confused with loss of fitness and ability to perform activities of daily living. Although a degree of loss of fitness does occur with increasing age, this can be prevented to a certain degree and certainly delayed with physical activity. Exercise attenuates sarcopenia, which supports bone mineral density with the added benefit of improved proprioception, helping to reduce risk of falls and potential fracture; not to mention the psychological benefits of exercise.

References

Genome-wide meta-analysis associates HLA-DQA1/DRB1 and LPA and lifestyle factors with human longevity Nature Communications 2017

Physical activity and telomere length in U.S. men and women: An NHANES investigation Preventive Medicine 2017

The landscape of sex-differential transcriptome and its consequent selection in human adults BMC Biology 2017

Temporal considerations in Endocrine/Metabolic interactions Part 1 British Journal of Sport and Exercise Medicine, October 2017

Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting Obesity 2017

Temporal considerations in Endocrine/Metabolic interactions Part 2 British Journal of Sport and Exercise Medicine, October 2017

Time-restricted eating may yield moderate weight loss in obesity Endocrine Today 2017

The Effect of Postexercise Carbohydrate and Protein Ingestion on Bone Metabolism Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine 2017

Periodized Nutrition for Athletes Sports Medicine 2017

Internal Biological Clocks and Sport Performance British Journal of Sport and Exercise Medicine, October 2017

Nutritional support for injuries requiring reduced activity Sports in Science Exchange 2017

Balance fat and muscle to keep bones healthy, study suggests NTU October 2017

Dietary Protein Intake above the Current RDA and Bone Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2017

Too little sleep and an unhealthy diet could increase the risk of sustaining a new injury in adolescent elite athletes Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports

Sleep for health and sports performance British Journal of Sport and Exercise Medicine, 2017

The impact of circadian phenotype and time since awakening on diurnal performance in athletes Current Biology

Successful Ageing British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine 2017

Focus on physical activity can help avoid unnecessary social care BMJ October 2017

Biochemical Pathways of Sarcopenia and Their Modulation by Physical Exercise: A Narrative Review Frontiers in Medicine 2017