Optimal health: for all athletes! Part 4 Mechanisms

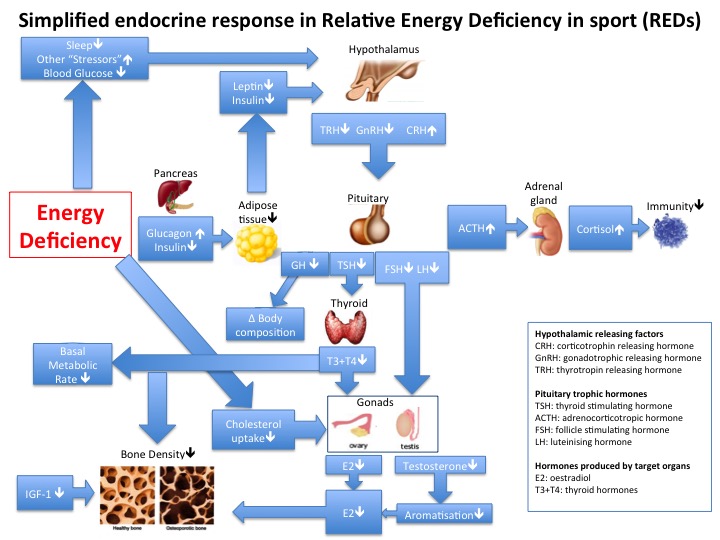

As described in previous blogs, the female athlete triad (disordered eating, amenorrhoea, low bone mineral density) is part of Relative Energy Deficiency in sports (RED-S). RED-S has multi-system effects and can affect both female and male athletes together with young athletes. The fundamental issue is a mismatch of energy availability and energy expenditure through exercise training. As described in previous blogs this situation leads to a range of adverse effects on both health and sports performance. I have tried to unravel the mechanisms involved. Please note the diagram below is simplified view: I have only included selected major neuroendocrine control systems.

Low energy availability is an example of a metabolic stressor. Other sources of stress in an athlete will be training load and possibly inadequate sleep. These physiological and psychological stressors input into the neuroendocrine system via the hypothalamus. Low plasma glucose concentrations stimulates release of glucagon and suppression of the antagonist hormone insulin from the pancreas. This causes mobilisation of glycogen stores and fat deposits. Feedback of this metabolic situation to the hypothalamus, in the short term is via low blood glucose and insulin levels and in longer term via low levels of leptin from reduced fat reserves.

A critical body weight and threshold body fat percentage was proposed as a requirement for menarche and subsequent regular menstruation by Rose Frisch in 1984. To explain the mechanism behind this observation, a peptide hormone leptin is secreted by adipose tissue which acts on the hypothalamus. Leptin is one of the hormones responsible for enabling the episodic, pulsatile release of gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) which is key in the onset of puberty, menarche in girls and subsequent menstrual cycles. In my 3 year longitudinal study of 87 pre and post-pubertal girls, those in the Ballet stream had lowest body fat and leptin levels associated with delayed menarche and low bone mineral density (BMD) compared to musical theatre and control girls. Other elements of body composition also play a part as athletes tend to have higher lean mass to fat mass ratio than non-active population and energy intake of 45 KCal/Kg lean mass is thought to be required for regular menstruation.

Suppression of GnRH pulsatility, results in low secretion rates of pituitary trophic factors LH and FSH which are responsible for regulation of sex steroid production by the gonads. In the case of females this manifests as menstrual disruption with associated anovulation resulting in low levels of oestradiol. In males this suppression of the hypothamlamic-pituitary-gonadal axis results in low testosterone production. In males testosterone is aromatised to oestradiol which acts on bone to stimulate bone mineralisation. Low energy availability is an independent factor of impaired bone health due to decreased insulin like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) concentrations. Low body weight was found to be an independent predictor of BMD in my study of 57 retired pre-menopausal professional dancers. Hence low BMD is seen in both male and female athletes with RED-S. Low age matched BMD in athletes is of concern as this increases risk of stress fracture. In long term suboptimal BMD is irrecoverable even if normal function of hypothamlamic-pituitary-gonadal function is restored, as demonstrated in my study of retired professional dancers. In young athletes RED-S could result in suboptimal peak bone mass (PBM) and associated impaired bone microstructure. Not an ideal situation if RED-S continues into adulthood.

Another consequence of metabolic, physiological and psychological stressor input to the hypothalamus is suppression of the secretion of thyroid hormones, including the tissue conversion of T4 to the more active T3. Athletes may display a variation of “non-thyroidal illness/sick euthyroid” where both TSH and T4 and T3 are in low normal range. Thyroid hormone receptors are expressed in virtually all tissues which explains the extensive effects of suboptimal levels of T4 and T3 in RED-S including on physiology and metabolism.

In contrast, a neuroendocrine control axis that is activated in RED-S is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. In this axis, stressors increase the amplitude of the pulsatile secretion of CRH, which in turn increases the release of ACTH and consequently cortisol secretion from the adrenal cortex. Elevated cortisol suppresses immunity and increases risk of infection. Long term cortisol elevation also impairs the other hormone axes: growth hormone, thyroid and reproductive. In other words the stress response in RED-S amplifies the suppression of key hormones both directly and indirectly via endocrine network interactions.

The original female athlete triad is part of RED-S which can involve male and female athletes of all ages. There are a range of interacting endocrine systems responsible for the multi-system effects seen in RED-S. These effects can impact on current and future health and sports performance.

For further discussion on Endocrine and Metabolic aspects of SEM come to the BASEM annual conference 22/3/18: Health, Hormones and Human Performance

References

Teaching module on RED-S for BASEM as CPD for Sports Physicians

Optimal health: including female athletes! Part 1 Bones Dr N. Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine

Optimal health: including male athletes! Part 2 Relative Energy Deficiency in sports Dr N.Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine 4/4/17

Optimal health: especially young athletes! Part 3 Consequences of Relative Energy Deficiency in sports Dr N. Keay, British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine

Keay N, Fogelman I, Blake G. Effects of dance training on development,endocrine status and bone mineral density in young girls. Current Research in Osteoporosis and bone mineral measurement 103, June 1998.

Jenkins P, Taylor L, Keay N. Decreased serum leptin levels in females dancers are affected by menstrual status. Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society. June 1998.

Keay N, Dancing through adolescence. Editorial, British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol 32 no 3 196-7, September 1998.

Keay N, Effects of dance training on development, endocrine status and bone mineral density in young girls, Journal of Endocrinology, November 1997, vol 155, OC15.

Relative Energy Deficiency in sport (REDs) Lecture by Professor Jorum Sundgot-Borgen, IOC working group on female athlete triad and IOC working group on body composition, health and performance. BAEM Spring Conference 2015.

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, Meyer N, Sherman R, Steffen K, Budgett R, Ljungqvist A. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad-Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S).Br J Sports Med. 2014 Apr;48(7):491-7.

“Subclinical hypothydroidism in athletes”. Lecture by Dr Kristeien Boelaert at BASEM Spring Conference 2014 on the Fatigued Athlete

From population based norms to personalised medicine: Health, Fitness, Sports Performance Dr N. Keay, British Journal of Sport Medicine

It is hard to dispute that women are underrepresented in medical research and certainly there are not many studies that include female athletes. Does this matter? After all whatever your gender the same physiological and metabolic processes occur. However the Endocrine system is where there are distinct differences in sex steroid production, which in turn have different responses in multiple target cells.

It is hard to dispute that women are underrepresented in medical research and certainly there are not many studies that include female athletes. Does this matter? After all whatever your gender the same physiological and metabolic processes occur. However the Endocrine system is where there are distinct differences in sex steroid production, which in turn have different responses in multiple target cells.