The state of play on relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs): Psychological aspects

Abstract

This article explores the current state of play regarding relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs), highlighting the recent updates from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement September 2023. Psychological factors and mental health are recognised as having a reciprocal relationship in both the aetiology and outcome of chronic low energy availability leading to REDs. This has important implications in terms of prevention and management of individuals experiencing REDs. Unintentional or intentional unbalanced behaviours around exercise and nutrition leads to a situation of low energy availability. Low energy availability is not synonymous with REDs. Rather cumulative, sustained low energy availability, particularly low carbohydrate availability, leads to the clinical syndrome of REDs comprising a constellation of adverse consequences on all aspects of health and performance. This situation can potentially arise in both biological sexes, all ages and level of exerciser. This is of particular concern for the young aspiring athlete or dancer, where behaviours are being established and in terms of long-term consequences on mental and physical health. The mechanism of sustained low energy availability leading to these negative health outcomes is through the adaptive down regulation of the endocrine networks. Therefore, raising awareness of the risk of REDs and implementing effective prevention and identification strategies is a high priority.

Introduction

Relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs) was first described in the International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement published in the British Journal of Sports and Exercise Medicine (BJSM) 2014 (Mountjoy, 2014). Since then, there have been updates published in 2018 (Mountjoy, 2018) and most recently in September 2023 (Mountjoy, 2023).

Seminal studies of female collegiate runners in 1980s found that those athletes with higher weekly training load, but same food intake as those with lower training load, experienced menstrual disruption, including secondary amenorrhoea and poor bone health (Drinkwater, 1984). This led to the description of the female athlete triad, which comprises a clinical spectrum of eating patterns, menstrual function and bone health. This ranges from optimal fuelling, menstrual function and bone health; to eating disorders, amenorrhoea and osteoporosis.

However, with further evidence emerging it became apparent that the impact of under fuelling is not confined to menstrual and bone health. Rather that the consequences of under fuelling are multisystem and can include male athletes. This led to the initial description of REDs in 2014 as a syndrome comprised of the potential adverse effects on many systems in the body with both physical and mental health implications. Crucially, unlike the female athlete trad, REDs also included the potential negative sequalae on athletic performance. Ultimately the goal for all athletes is to perform to their best, so REDs is not something of interest just in academic or clinical circles. REDs is highly relevant to both biological sexes and all levels and ages of exerciser.

What is Energy Availability?

The underlying aetiology of REDs is low energy availability. The life history theory describes how biological processes compete for energy resources (Shirley, 2022). Energy requirement for movement is prioritised from an evolutionary point of view in order to take evasion action from predators. The residual energy from food intake is described as energy availability. This is roughly equivalent to resting metabolic rate for the individual. Simply lying in bed all day, staying alive, is high energy demand for humans as homeotherms. The numerical value of energy availability is expressed in Kcals/Kg of fat free mass. The energy availability requirement for health will vary between individuals depending on sex, age and body composition. Although energy availability is a very useful concept, in practice is it not actually measured outside of the research setting. Rather objective surrogates indicating energy availability can be measured such as triiodothyronine (T3) which is used as a primary indicator of low energy availability as outlined in the update REDs clinical assessment tool described in further detail below (Stellingwerff, 2023 ).

An important highlight from the updated consensus statement on REDs is that it is specifically low carbohydrate availability that is most detrimental, especially for reproductive hormone networks. Comparing isocaloric intake, where there is a low proportion of energy from carbohydrate, this has the most marked negative consequence on both hormone health and performance. The mechanism of sustained low carbohydrate availability appears to involve the hormone leptin, an adipokine, secreted by adipose tissue. Low levels of leptin cause suppression of the reproductive axis via the hypothalamus-pituitary axis (Keay, 2022).

Aetiology of Low Energy Availability

Low energy availability is a situation where, once energy demand from movement has been met, the residual energy available is insufficient to support the functioning of other biological life process.

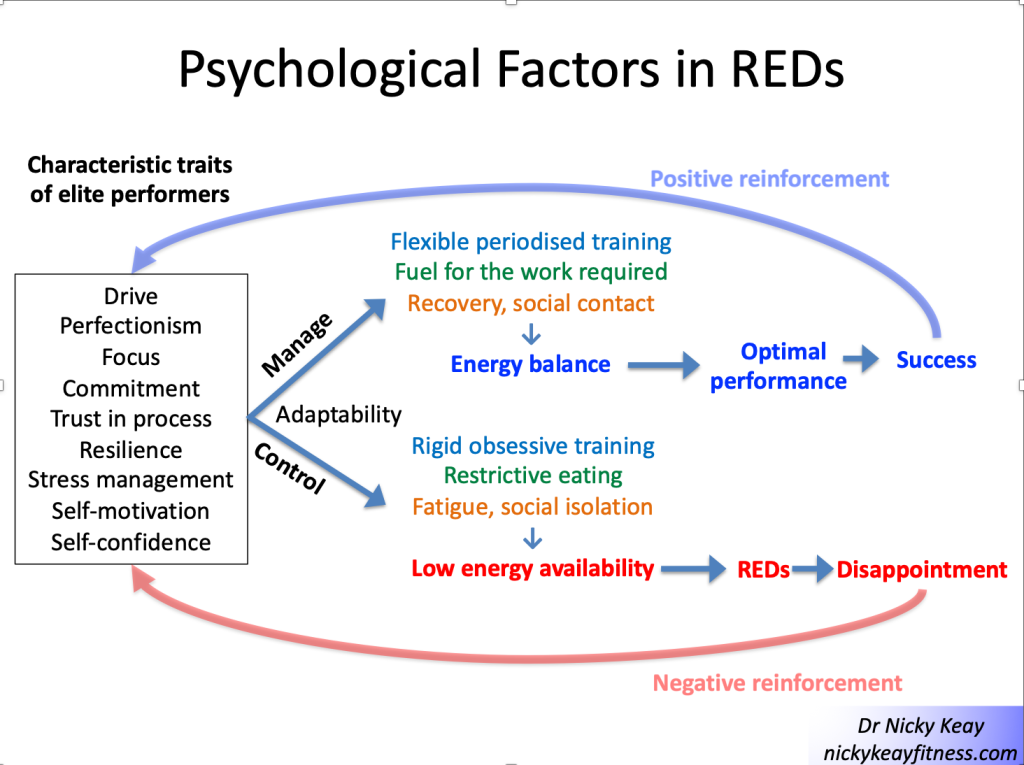

Low energy availability could arise unintentionally or intentionally (Keay, 2019). Unintentional low energy availability is where an exerciser does not appreciate the energy demands of exercise and other activities with an energy demand. For example, many athletes will not consider the energy required to “commute” to a training session on foot or bike. Unintentional low energy availability could be due to practical issues: for example, a long cycle ride over several hours will require the cyclist to take nutritional sources in the pockets of clothing and/or plan ahead suitable stops where it is possible to obtain nutrition. Similarly, going on a training camp, especially at altitude, will greatly increase energy demand from exercise and needs to factored in. Finances could also be a limiting factor.

On the other hand, intentional low energy availability is where an exerciser intentionally restricts nutrition intake in the belief that this might confer a performance advantage in terms of body weight, composition or shape. This is particularly associated with any exercise against gravity such as running, road cycling, climbing; weight category sports like martial arts and aesthetic forms of sport (diving, gymnastics) and dance.

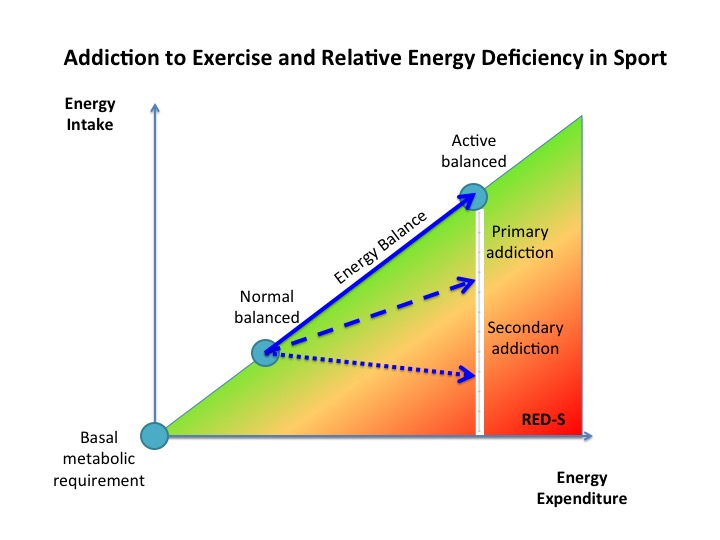

For individuals with intentional low energy availability, psychology and mental health can have a reciprocal interaction (Pensgaard, 2023). Those exercisers with personality characteristics such as self-motivation, perfectionism can be very laudable traits in terms of dedication to exercise training to achieve success. However, when these characterises impact and support rigid behaviours around training and nutrition, this can become problematic. This is shown in Figure 1 “Psychological factors in REDs”. Those who are able to adapt to external pressures and have a flexible approach to training and nutrition are more likely to experience positive outcomes. Whereas those who have a more rigid approach, which might include disordered eating and or an eating disorder and/or exercise dependence are more likely to experience negative outcomes. This reinforces self-doubt and culminates in a vicious circle of perpetuating rigid behaviours and negative outcomes in terms of both physical and mental health.

Evidence for this interaction between psychological factors and risk of REDs was found in our study of dancers, referenced in the updated IOC consensus statement. A significant relationship was found between psychological factors such as anxiety around body shape/weight and missing training. These psychological factors in turn had significant associations between physical manifestations of low energy availability (low body weight) and physiological outcomes (menstrual irregularity) (Keay, 2020). Similarly, in more of our published research papers referenced in the IOC consensus statement focusing on male athletes, an significant association was found between cognitive nutritional restraint and negative physiological and performance outcomes (Jorov, 2021).

This reciprocal interaction between internal and external factors is a systems biology approach, highlighted in the recent updated IOC consensus statement. From a physiological point of view the brain is a high energy demand organ, requiring a good supply of glucose. So low carbohydrate availability will restrict this cerebral supply, which can impair cognitive function and ultimately good decision making. It is interesting to reflect that the neuroendocrine gatekeeper, the hypothalamus keeps a watching brief on internal and external factors, not distinguishing between the source of stressors when putting in motion an adaptive response (Keay, 2022).

Consequences of Low Energy Availabiity

Low energy availability is not synonymous with REDs. Indeed, short term low energy availability might initially bring some good performances. Low energy availability becomes problematic depending on the time scale, which in turn determines the degree of adaptive response, described in the clinical physiological model of REDs (Burke, 2023). The first system to adapt to low energy availability is bone: bone turnover moves in favour of resorption over formation. This is why bone stress responses, specifically bone stress fractures, can be an early warning sign of REDs and designated a primary indicator in the updated IOC consensus statement. There will follow sequential down regulation of metabolic rate mediated via the thyroid axis, followed by the reproductive axis. In women primary amenorrhoea or sustained functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea (FHA) of 6 months or more duration is a severe primary indicator of REDs. In men, low rage testosterone is a severe primary indicator. Ultimately body composition will be adversely affected, with the only endocrine system to be up regulated being that of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Keay, 2019).

Health

Cumulative low energy availability causes the syndrome of REDs, which produces progressive adverse effects on all aspects of health: physical, mental and social, described in the REDs conceptual model. Poor sleep will compound these negative health effects (Keay, 2022).

Performance

Although there may be some initial good performances, chronic low energy availability will result in adverse performance consequences of REDs, described in the REDs performance conceptual model. In our referenced papers in the consensus statement, we found that in male athletes, short term low energy availability impacted performance (Jurov, 2022). In another of our referenced studies we showed that male cyclists in sustained low energy availability over 6 months, not only experienced bone loss commensurate to astronauts in space, but these cyclists also underperformed compared to their energy replete fellow cyclists (Keay, 2019). On a positive note, explaining to athletes and dancers that improving energy availability will improve their performance, can help in overcoming problematic behaviours.

Identification of those at risk

In view of the potential adverse health and performance effects of REDs, it is a priority to raise awareness of this risk to affect prevention. To this end the British Association of Sports and Exercise Medicine (BASEM) has a website health4performance.co.uk dedicated to providing reliable information on REDs for athletes, parents, coaches and health care professionals together with BASEM endorsed online courses. Targeting and identifying those at increased risk is very important. Young athletes and dancers can be most severely affected as down regulation of hormone function due to low energy availability can cause delay in growth and development. In particular, delayed puberty and menarche dampens the accrual of peak bone mass, with implications for bone health (Keay, 2000). Furthermore, there is evidence that these adverse effects on bone health might not be fully reversible (Keay, 1997)

From a psychological point of view, the young aspiring athlete and dancer is also at heightened risk. Explored and viewed by many dancers in “The Dark Side of Ballet Schools” Panorama (season 33, episode 28). Selection for specialised training will inevitably favour those who are self-motivated and dedicated. In a group of individuals sharing similar psychological traits this could act as a “breeding ground” for reinforcing these characteristics in ways that could lead to behaviours which are not conducive to positive outcomes. Rather reinforcing the negative interpretation of external and internal factors, leading to a vicious circle of reinforcing attitudes and behaviours leading to REDs, as described in Figure 1

Risk stratification

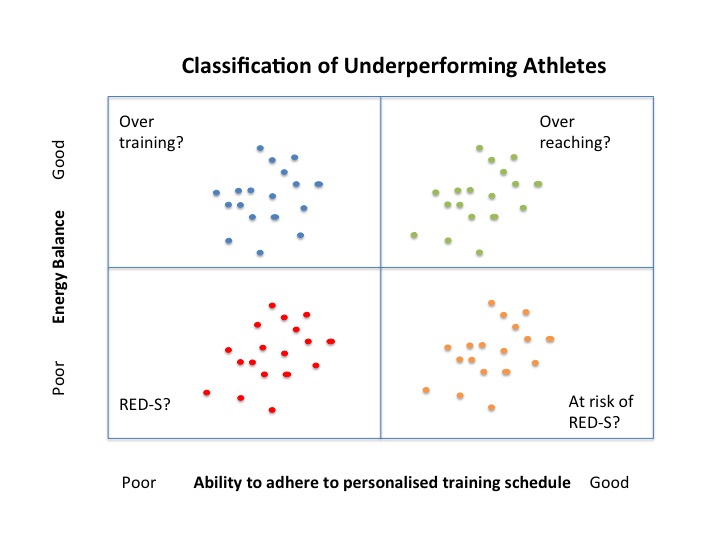

Early identification of those at risk of developing REDs is an important preventative strategy. Especially for young aspiring athletes and dancers where behaviours around eating and exercise are being developed and established. A step-by-step approach is provided in the updated version 2 of the Relative Energy Deficiency in sport Clinical Assessment Tool (REDsCat v2) to identify and risk stratify individuals (Stellingwerff, 2023 ). Initial, low cost, screening questionnaires can be helpful, particularly if tailored to a specific sport/activity or dance. For example: sports specific energy availability questionnaire (SEAQ) (Keay, 2018) and dance energy availability energy questionnaire (DEAQ) (Keay, 2020). This can be helpful in identifying those individuals where further investigation is clinically indicated. As REDs is a diagnosis of exclusion, targeted blood testing excludes medical conditions per se and provide objective quantification in the stratification of risk. Severe primary indicators of REDs are issues in the reproductive axis: long duration of amenorrhoea in females and low range testosterone in males.

From a combination of all these results the individual can be placed in an appropriate risk category. The updated REDs CAT v2 includes a finer grained approach with four categories from green, yellow, amber to red.

This assessment also provides the background on which to base the appropriate level of support. For all, management will be directed at restoring energy availability and include modification of training and nutritional intake. However, the details will vary according to the severity of REDs. Individuals with intentional REDs, especially when formally diagnosed with an eating disorder, will need most intensive input than a person with transient unintentional low energy availability.

Management

A nuanced approach is required for individual athletes, depending on their risk stratification and biopsychosocial factors. In all cases some degree of psychological support will be helpful. Involvement of the extended multidisciplinary team is ideal: medical doctor, dietician, coach and parent (where appropriate) with the athlete/dancer at the centre.

In order to restore energy availability this will require careful discussion around nutrition in terms of consistency of eating patterns and composition of food groups consumed. This starts with regular meals containing good portions of complex carbohydrate and protein. Studies show that inconsistent intake of carbohydrate (eg “backloading” eating to the evening) produces an unfavourable hormone profile. Fuelling around training is also a high priority for hormone health and driving positive adaptations to exercise. Pre training consumption of carbohydrate together with post training refuelling with both complex carbohydrate and protein within 20 minutes of stopping are important behaviours for favourable hormone response to exercise (Keay, 2022).

In terms of pharmacological intervention, NICE guidelines have been updated 2022 in recommending body identical hormone replacement therapy (HRT) over the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) for bone protection in those with evidence of bone poor health due to functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea (FHA) as a consequence of REDs (BASEM, 2023). Poor bone health is defined as age matched Z score < -1 of the lumbar spine (trabecular bone particularly sensitive to low oestradiol) and/or 2 or more stress fractures at a site of concern (trabecular rich bone). For male athletes/dancers external testosterone is not appropriate as this supresses internal hormone production. Furthermore, testosterone is on the world anti-doping authority (WADA) banned list and it is not possible to obtain a therapeutic use exemption (TUE) as REDs is a functional condition, not a medical condition.

Prevention

Prevention is always the ultimate goal. In order to achieve this aim, a cultural shift in sport and dance is required. Emphasis on the fact that health is a prerequisite for performance. Pursuing a lighter body weight or leaner body composition will not automatically lead to improved performance. Each individual will have a personal tipping point. As we are all different, there is no such thing as a generic “ideal” weight/shape/body composition.

In practical terms, prevention can be considered as primary, secondary and tertiary (Torstveit, 2023). Primary prevention consists of providing and disseminating reliable educational resources. Secondary prevention includes early identification of those at risk of developing REDs, together with prompt and correct diagnosis. For example, regardless of whether an athlete or dancer, amenorrhoea in a woman of reproductive age (apart from physiological amenorrhoea of pregnancy) is never “normal”; whether blood tests are in range, or not. The tertiary level of prevention encompasses evidence-based treatments. As mentioned above, NICE guidelines are now in line with Endocrine Society and IOC in advising temporising HRT for bone protection in FHA. Not the COCP which masks underlying hormone dysfunction and is not bone protective. Similarly, thyroxine is not advised where there is downregulation of this axis as a consequence of REDs. This is not the same as the medical condition of a primary underactive thyroid indicated by raised thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) (Keay, 2022).

Conclusion

Ultimately, we all have a role to play in supporting exercisers, athletes and dancers in avoiding “the REDs card” (Mountjoy, 2023). This involves the extended multidisciplinary team, starting with the individual exerciser, family, friends and coaches. Then bringing in health care professionals from medicine, dietetics and physiotherapy.

Imbalances in behaviours around exercise and nutrition can have potential negative consequences on all aspects of health and performance. On a positive note, exercise, supported with appropriate nutrition, is an excellent way to achieve and maintain optimal physical, mental and social health and support performance. This is applicable for all ages and levels of exercisers from the recreational to the amateur and elite athlete.

References

Burke LM, Ackerman KE, Heikura IAet al. Mapping the complexities of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs): development of a physiological model by a subgroup of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Consensus on REDs British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:1098-1108.

Drinkwater B, Nilson K, Chesnut C. Bone Mineral Content of Amenorrheic and Eumenorrheic Athletes N Engl J Med 1984; 311:277-281 DOI: 10.1056/NEJM198408023110501

Jurov I, Keay N, Hadžić V et al. Relationship between energy availability, energy conservation and cognitive restraint with performance measures in male endurance athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2021;18:24. doi:10.1186/s12970-021-00419-3

Jurov I, Keay N, Spudić D et al. Inducing low energy availability in trained endurance male athletes results in poorer explosive power. Eur J Appl Physiol 2022;122:503–13. doi:10.1007/s00421-021-04857-4

Keay N Hormones, Health and Human Potential: A guide to understanding your hormones to optimise your health and performance 2022 Sequoia books

Keay N, Overseas A, Francis G. Indicators and correlates of low energy availability in male and female dancers BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2020;6:e000906. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000906

Keay N, Francis G. Infographic. Energy availability: concept, control and consequences in relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53:1310-1311.

Keay N, Rankin A. Infographic. Relative energy deficiency in sport: an infographic guide

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53:1307-1309.

Keay N, Francis G, Hind K. Low energy availability assessed by a sport-specific questionnaire and clinical interview indicative of bone health, endocrine profile and cycling performance in competitive male cyclists BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2018;4:e000424. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000424

Keay N, Francis G, Entwistleet al. Clinical evaluation of education relating to nutrition and skeletal loading in competitive male road cyclists at risk of relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S): 6-month randomised controlled trial BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2019;5:e000523. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000523

Keay N. The modifiable factors affecting bone mineral accumulation in girls: the paradoxical effect of exercise on bone. Nutrition Bulletin 2000, 25: 219-222. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-3010.2000.00051.x

Keay N, Fogelman I, Blake G. Bone mineral density in professional female dancers.

British Journal of Sports Medicine 1997;31:143-147.

Mountjoy M, Ackerman KE, Bailey Det al. 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:1073-1097.

Mountjoy M, Ackerman KE, Bailey Det al. Avoiding the ‘REDs Card’. We all have a role in the mitigation of REDs in athletes British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:1063-1064.

Pensgaard AM, Sundgot-Borgen J, Edwards Cet al. Intersection of mental health issues and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs): a narrative review by a subgroup of the IOC consensus on REDs British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:1127-1135.

Stellingwerff T, Mountjoy M, McCluskey Wet al. Review of the scientific rationale, development and validation of the International Olympic Committee Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport Clinical Assessment Tool: V.2 (IOC REDs CAT2)—by a subgroup of the IOC consensus on REDs British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:1109-1118.

International Olympic Committee relative energy deficiency in sport clinical assessment tool 2 (IOC REDs CAT2) British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:1068-1072.

Shirley M, Longman D, Elliott-Sale K et al. A Life History Perspective on Athletes with Low Energy Availability. Sports Med 2022 52, 1223–1234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01643-w

Todd E, Elliot N, Keay N. Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) British Journal of General Practice 2022; 72 (719): 295-297. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp22X719777

Torstveit M, Ackerman K, Constantini N et al. Primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs): a narrative review by a subgroup of the IOC consensus on REDs Br J Sports Med 2023;57:1119–1126.