Athletic Fatigue: Part 2

A degree of athletic fatigue following a training session, as described in part 1, is required to set in motion mechanisms to drive beneficial adaptations to exercise. At what point does this process of functional over-reaching tip into non-functional over-reaching denoted by failure to improve sports performance? Or further still along the spectrum and time scale, the chronic situation of overtraining and decrease in performance? Is this a matter of time scale, or degree, or both?

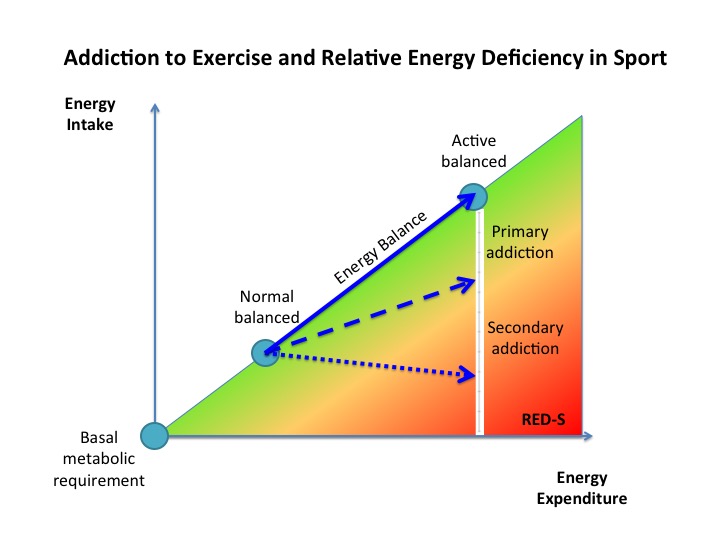

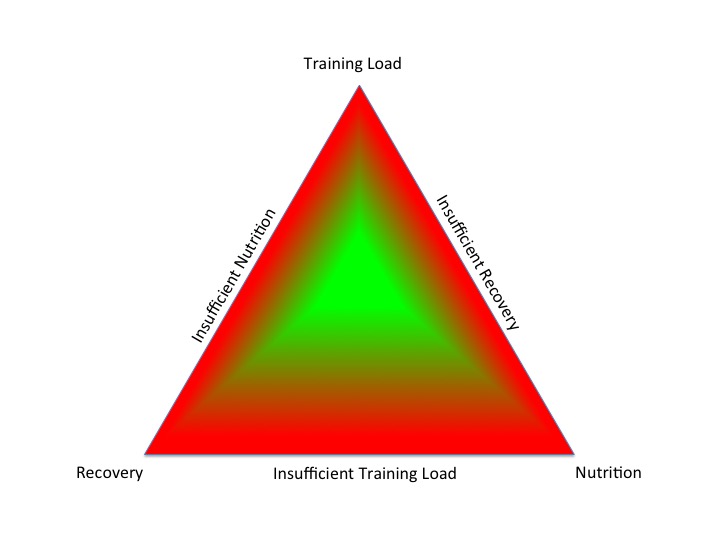

- Integrated Periodisation of Training Load, Nutrition and Recovery keeps an individual on the green plateau, avoiding descent into the red zone, due to an excess or deficiency

Determining the tipping point between these fatigue situations is important for health and performance. A first step is always to exclude underlying organic disease states, be these of Endocrine, systemic inflammatory or infective aetiologies. Thereafter the crucial step is to assess whether the periodisation of training, nutrition and recovery are integrated over a training block and in the longer term over a training season.

What about the application of Endocrine markers to monitor training load? Although the recent studies described below are more applicable to research scenarios, they give some interesting insights into the interactive networks effects of the Endocrine system and the multifactorial nature of fatigue amongst individual athletes.

In the short term, during a 2 day rowing competition, increases in wakening salivary cortisol were noted followed by return towards baseline in subsequent 2 day recovery. Despite individual variability with salivary cortisol measurement, this does at least offer a noninvasive way to adjust training loads around competition time for elite athletes.

Over an 11 day stimulated training camp and recovery during the sport specific preparatory phase of the training season, blood metabolic and Endocrine markers were measured. In the case of an endurance based training camp in cyclists, a significant increase in urea (due to protein breakdown associated with high energy demand training) and decrease in insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) from baseline were noted. Whereas for the strength-based athletes for ball sports, an increase in creatine kinase (CK) was seen, as a result of muscle damage. This study demonstrates how different markers of fatigue are specific to sport discipline and mode of training. Large inter-individual variability existed between the degree of change in markers and degree of fatigue.

In the longer term, for the case of overtraining syndrome potential Endocrine markers have been reviewed. Whilst basal levels of most measured hormones remained stable, a blunted submaximal exercise response of growth hormone (GH), prolactin and ACTH could be indicative of developing overtraining syndrome. Whilst this review is interesting, dynamic testing is not a practical approach and these findings are not specific to over training. Rather this blunted dynamic exercise response would indicate relative suppression of the neuroendocrine hypothalamic-pituitary axis which could potentially involve other stressors such as inadequate sleep or poor nutrition. Although basal levels may lie “within the normal range”, if both pituitary derived stimulating hormone and end endocrine gland hormone concentrations fall in the lower end of the normal ranges (eg low end of range TSH and T4) this is consistent with mild hypothalamic suppression observed over the range of training and fatigue conditions (functional/non-functional and overtraining) and/or Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S).

Although the studies above are of research interest, non invasive monitoring, specific to an athlete is more practical for monitoring the effects of training. Several useful easily measurable metrics can give clues: resting heart rate, heart rate variability, power output. Tools on Strava and Training Peaks provide practical insights in monitoring training effectiveness via these metrics. A range of mobile apps makes it ever easier to augment a personal training log to include these training metrics, along with feel, sleep and nutrition. Such a log provides feedback on health and fitness for the individual athlete, in order to personalise training plans. Certainly adding the results from any standard basal blood tests will also help add to the picture, along the lines of building a longitudinal personal biological passport. After all, “normal ranges” are based on the general population, of which top level athletes may represent a subgroup. The more personalised the metics recorded over a long time scale, the more sensitive and useful the process to guide improvement in sport performance.

Context is key when considering athletic fatigue: temporal considerations and individual variation. Certainly the interactive network effects of the Endocrine system are important in determining the degree of adaptation to exercise and therefore sports performance. However the Endocrine system acts in conjunction with many other systems (metabolic, immune and inflammatory), in determining the effectiveness of training in improving sports performance. So it is not surprising that one metric or marker in isolation is not predictive of fatigue status in individual athletes.

References

Endocrine system: balance and interplay in response to exercise training

Temporal considerations in Endocrine/Metabolic interactions Part 1

Fatigue, sport performance and hormones..more on the endocrine system Dr N Keay, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017

Sport Performance and RED-S, insights from recent Annual Sport and Exercise Medicine and Innovations in Sport and Exercise Nutrition Conferences Dr N Keay, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017

Capturing effort and recovery: reactive and recuperative cortisol responses to competition in well-trained rowers British Journal of Sports Medicine

Blood-Borne Markers of Fatigue in Competitive Athletes – Results from Simulated Training Camps Plos One

Hormonal aspects of overtraining syndrome: a systematic review BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation 2017

Clusters of Athletes – A follow on from RED-S blog series to put forward impact of RED-S on athlete underperformance Dr N Keay, British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine 2017

Strava Fitness and Freshness Science4Performance 2017

From population based norms to personalised medicine: Health, Fitness, Sports Performance Dr N Keay, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017

Sports Endocrinology – what does it have to do with performance? Dr N Keay, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017