Hormone responses to exercise drive adaptive changes which impact health and performance. The nature of these adaptive changes will depend not only on the exercise training load. There will be individual variation in the nature of the endocrine response.

Given that female hormone networks are one of the most complex of all the endocrine systems, special consideration needs to be given to the exercising female population. Female hormones vary over the menstrual cycle and also change considerably over a woman’s lifespan. So, it is important to consider the detail of endocrine adaptations to exercise in the context of the temporal dimension: both the short term and long term. Furthermore, there will be individual differences in terms of gynaecological age, hormone levels, timings and biological response.

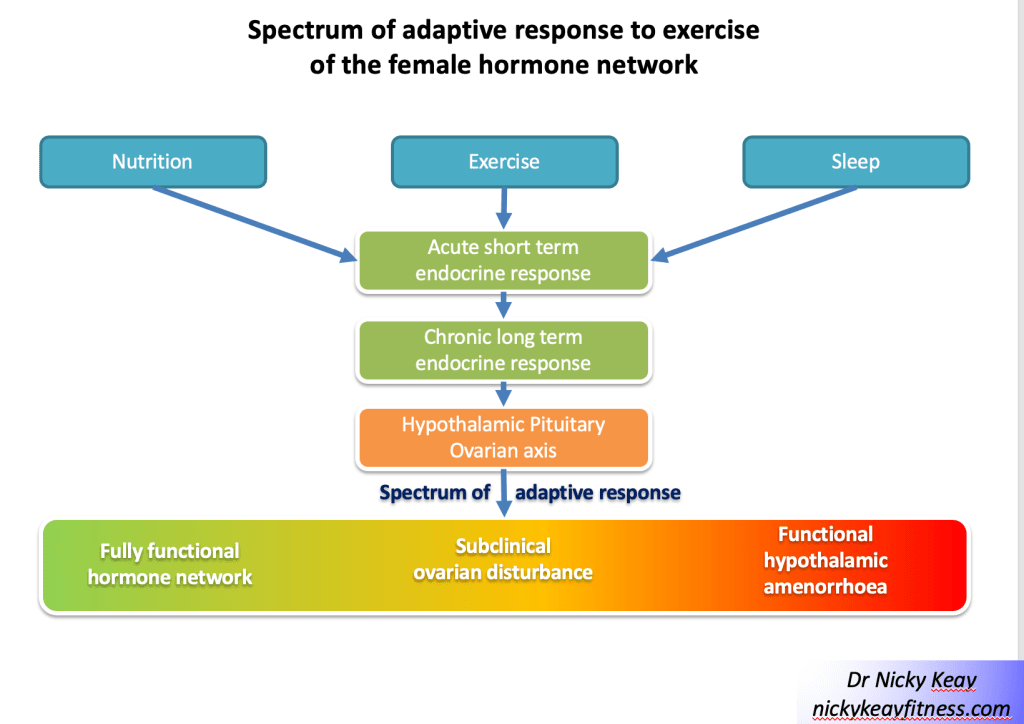

In addition to the effect of exercise training on hormone networks, these endocrine responses will be modulated by other lifestyle factors including the amount and timing of nutrition and recovery. To gain the most effective hormone response to exercise it is important to have an optimal combination of exercise, nutrition and recovery, appropriate for an individual. Any imbalances or mistiming in these external behavioural inputs can potentially lead to suboptimal and even negative hormone adaptations for health and performance.

This narrative opinion piece on exercise endocrinology focuses on the interactive effects of female hormones and exercise over lifespan.

Introduction

Hormones act by determining gene expression. Through this mechanism of action, hormones support homeostasis and are key determinants of all aspects of health. In addition, hormones interact with behaviours, including lifestyle choices around exercise, nutrition and sleep. In this way, hormone networks drive adaptations to exercise. We exercise in the hope and expectation that this will improve our health and fitness, which occurs through the action of hormones in the short term and long term over the lifespan[1].

“If we could give every individual the right amount of nourishment

and exercise, not too little and not too much, we would have found the

safest way to health.”

Hippocrates

Of all the hormone networks, the female hormones of the menstrual cycle are surely the most complex with intricate control mechanisms, including both positive and negative feedback loops. Furthermore, each woman will have individual hormone variations in terms of timing, concentration and biological response to these hormones. This why a personalised approach for each female exerciser is important to support the most beneficial endocrine adaptations to exercise.

Fluctuations in menstrual cycle hormones change over a woman’s lifespan, adding an extra layer of complexity in striving to optimise the interaction between exercise and internal hormones. Furthermore, exercise as a behaviour and lifestyle choice cannot be considered in isolation. Nutrition and sleep are other factors that interact with hormone networks. This triad of exercise, nutrition and sleep act in combination to determine endocrine adaptive responses[1].

This narrative opinion piece will explore the interactions of female hormone networks and exercise over a woman’s lifespan.

Female hormones and exercise interactions over the lifespan

Childhood

During childhood the hypothalamic-pituitary ovarian (HPO) axis is quiescent. This party explains why the energy systems required for anaerobic, intense exercise have not yet developed. For this reason, aerobic type exercise is advised during childhood to match the hormone milieu. Encouraging children to train like adults can lead to mental and physical “burnout”[2]. As girls have an earlier growth spurt than boys, girls are often faster in the 10-12 age group. Although moving into puberty and beyond, the higher levels of testosterone in men account for ergometric differences in exercise performance[3].

Adolescence

The HPO axis comes to life during puberty. The average age of menarche is around 12 years of age, although this may be a bit later in exercising young women. Nevertheless, failure of periods to start by age 15 years, primary amenorrhoea, necessitates medical investigation[4]. If no medical cause is found, a high exercise training load often combined with low energy intake, can be the aetiology of an adaptive down regulation of the HPO axis. This is a health concern as primary amenorrhoea will attenuate the accrual of peak bone mass (PBM), rendering young aspiring athletes at higher risk of bone stress injury with increasing training load when moving from junior to senior ranks[5]. From a study of retired, premenopausal dancers there is evidence that this adaptive down regulation of the reproductive axis can have a long term detrimental effect on bone health[6].

The reproductive years

Regular menstruation acts as barometer of internal hormone health. Menstrual cycle tracking can also help individual women to identify stages in the cycle when certain types of training might lead to the most positive athletic performance adaptations. For example, it has been suggested as beneficial to adaptation to perform strength training during the later follicular phase where oestradiol predominates and more endurance training during the luteal phase of the cycle where progesterone is the dominant ovarian hormone[7]. Nevertheless, the practical challenge is correctly identifying the timing of phases of the cycle associated with these hormone profiles. Although evidence indicates that the main source of temporal variability occurs during the follicular phase[8], even taking this into account there will be individual variation in terms of levels of hormones and biological response to these. Most likely these variations between women account for the finding of a null effect of the menstrual cycle on exercise performance from a large meta-analysis study[9] suggesting that statistical significance is not necessarily synonymous with clinical significance. This means a personalised approach is needed when matching up training and female hormones to gain the maximal positive adaptations for the individual female exerciser.

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea (FHA) is a lack of periods for 3 months or more where there is no underlying physiological or medical cause. The aetiology of FHA is down regulation at the hypothalamic level due to an imbalance of behaviours around exercise, nutrition, recovery and/or psychological factors. Female exercisers may experience FHA as an adaptive response to low energy availability.

Energy availability is the energy available from food intake, once the energetic demands of exercise have been subtracted. The value is expressed in Kcal/Kg of lean body mass, where sufficient energy availability is roughly equivalent to resting metabolic rate. Low energy availability arises as a result of an imbalance between energy intake and energy demand from exercise training, leaving insufficient energy to maintain health and performance[10]. Chronic low energy availability causes adaptive down regulation of many endocrine axes, including the HPO axis. This leads to the syndrome of relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S)[11]. In female exercisers, FHA is a clinical symptom of RED-S. FHA is a diagnosis of exclusion and so can be considered an adaptive response to exercise training where low energy availability prevails. From an evolutionary point of view, FHA is an energy conserving mechanism, which allows prioritisation of movement as an escape strategy from danger. However, the global adaptive down regulation of the endocrine system in RED-S has adverse effects on health and athletic performance in the long-term[12]

Although RED-S and overtraining syndrome (OTS) are often described as separate entities, in reality there is no hard dividing line[13]. External factors act in combination to influence hormone networks. Furthermore, the psychological element of how an individual interpretates events, impacts hormone function. In a study of dancers significant correlations were found between psychological factors and the relationship with physical characteristics and the physiological outcome of menstrual status[14]. Non-exercise related stressors were found to cause adaptive, functional neuroendocrine downregulation of the reproductive axis in military recruits participating in arduous training[15]. These findings demonstrate that psychological factors impact endocrine system function, in particular the female reproductive axis. This is why cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can help in restoration of full HPO axis function. Psychological factors need to be factored in when considering adaptive responses of the endocrine network to exercise in women.

Subclinical ovulatory disturbances as a spectrum of adaptive endocrine responses

FHA is a very obvious clinical indication of endocrine dysregulation. However, in subclinical ovulatory disturbances, regular periods may belie a down regulatory adaptive response[16]. Subclinical ovulatory disturbances encompass a spectrum of adaptive changes in the HPO axis in response to an imbalance of external inputs around exercise, nutrition and recovery. This is illustrated in Figure 1 Spectrum of adaptive response to exercise of the female hormone network.

The evolutionary purpose of the menstrual cycle is ovulation for reproduction. However, the action of the ovarian hormones associated with the menstrual cycle go far beyond reproduction. Oestradiol is well recognised as vital for many areas of health encompassing the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, neurological and gastrointestinal systems. Less well recognised is the importance of progesterone, particularly for bone and cardiovascular health[17]. This is why it is crucial to consider the detail of any adaptive changes of the HPO axis to the combinations of exercise training, nutrition and recovery. Furthermore, tracking menstrual cycles alone may not be sufficient as a training metric to assess adaptation to exercise training.

Assessing the details of the menstrual cycle hormone profile would provide insights into the nature and degree of endocrine adaptation of the HPO axis. Although saliva and urine provide convenient mediums from which to measure hormones, these are limited to analysis of steroid hormones in the case of saliva and in urine metabolites for some of the female hormones. The gold standard way of assessing the “full house” of menstrual cycle hormones: follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinising hormone (LH), oestradiol and progesterone is from a blood sample. Measuring both pituitary and ovarian hormones is important in order to distinguish between hypothalamic and ovarian causes of suspected subclinical ovulatory disturbances. When combined with an exercise specific screening questionnaire and clinical interaction, this approach was found to be effective and well received from female athletes in a longitudinal study of dancers in a professional dance company[18] and in professional female football players[19].

Assessment of menstrual hormone health, using the non-invasive method of Quantitative Basal Temperature (QBT) has been extensively researched and validated[20]. This is based on the principle that progesterone, produced during the luteal phase increases metabolic rate and has a thermogenic effect. However, low levels of progesterone, as found in subclinical ovulatory disturbances, will not be sufficient to produce a sustained increase in body temperature. Low progesterone will prevent an increase in metabolic rate and consequent increased energy intake requirement. Therefore, low progesterone production during the luteal phase, can be considered as an adaptive response to stressors; whether thee stressors arise from high training load, low energy availability or other psychological factors[16].

Further ongoing research will help identify subtle adaptive changes to exercise in the female endocrine system. A validated clinical tool, drawing on a number of inputs, will support the early detection, and monitoring of recovery from, down regulatory adaptive responses of the HPO axis. An example of passing the baton between increasing understanding of the interactions between exercise and the endocrine system[21].

Management of hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis down regulation

Where any degree of adaptive functional endocrine down regulation is detected, the priority is to rebalance the factors of training load, nutrition and recovery to restore full HPO axis function to support optimal health and performance. Psychological support may also be needed to facilitate behavioural change, especially in the case of intentional low energy availability. Depending on the status of bone health in FHA, pharmacological bone protection may be indicated. Although exercise has a positive osteogenic effect on bone, this is negated in the presence of down regulated adaptive endocrine response. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement advises treatment with transdermal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in female exercisers with FHA and 2 or more stress fractures, or a Z score of less than -1 of the lumbar spine[22]. The lumbar spine being trabecular bone is especially sensitive to suboptimal endocrine and nutritional status. The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) is not suitable for bone protection as this reinforces down regulation of the HPO axis[23]. Nevertheless, HRT for bone protection is a temporising measure while support is being provided to modify behaviours to ensure health and beneficial endocrine adaptations to exercise.

Intracrinology as a hormone adaptation to exercise?

A novel form of exercise induced hormone adaptation could be attributable to intracrinology. This is the process whereby there is cell specific production of androgens from the precursor DHEA. Androgens produced in this way have a site-specific effect[24]. In answer to the question of whether athletes are born or made, it could be that this intracrine adaptive response could go some way to explaining why higher levels of DHEA, anabolic body composition and performance measures were found on Olympic athletes compared to sedentary controls[25].

Hormonal contraception

It is every woman’s personal choice whether to take hormonal contraception, or not. There are some medical conditions where suppression of ovulation with hormonal contraception can be a helpful management strategy. For example, in the situation of conditions “fuelled” by fluctuation in female hormones such as endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). On the other hand, there are situations where hormonal contraception is not appropriate, such as in FHA as outlined above. The jury is still out as to whether hormonal contraception has an effect on endocrine adaptations to exercise and subsequent athlete performance. As with anything to do with female hormones, this is very variable according to the individual. Furthermore, there are such a vast range of hormonal contraceptive preparations, that it is virtually impossible to make generalisations about the impact of hormonal contraception on endocrine adaptation to exercise.

Graduation to menopause

The graduation to menopause marks an important point in a woman’s life when her ovaries stop producing eggs and ovarian hormones. In the face of the changing backdrop of female hormones, the nature of lifestyle factors, including exercise will need to be reconsidered in order to benefit from adaptative changes. Exercise remains the cornerstone and has been shown to help alleviate menopausal symptoms, in particular thermoregulatory issues[26]. Furthermore exercise, with a focus on strength training supports metabolic health[27], body composition[28] and bone strength[29], resisting the consequences of reduced production of sex steroid hormones. HRT can improve quality of life and reduce all-cause mortality, and for many women helps in maintaining their exercise levels[30]. In terms of preparations of HRT, transdermal oestradiol has the optimal profile for metabolic health and body identical oestradiol and micronised progesterone is available in licensed, regulated forms[31]. Testosterone can be given for hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). Although the aim is to restore testosterone to previous physiological levels, external testosterone cannot be taken by athletes competing in sporting events under world anti-doping authority (WADA) jurisdiction.

Conclusions

The interaction of female hormone function and exercise varies between individuals, resulting in a range of possible adaptive changes, both in the short and long term. As menstrual cycle hormones change over the lifespan, so does the response to exercise. Furthermore, exercise training should not be considered in isolation, rather in combination with other modifiable external factors such as nutrition and recovery. Psychological factors also play a part in determining responses of the female reproductive endocrine axis. It is important to characterise the nature of these endocrine adaptations, as not all will be favourable to health and performance. Therefore, a personalised approach is required when considering the interaction of exercise and female hormones.

References

[2] Bergeron MF, Mountjoy M, Armstrong N et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on youth athletic development. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015; 49: 843–851

[3] Hirschberg A. Female hyperandrogenism and elite sport, Endocrine Connections 2020, 9(4), R81-R92.

[4] Gordon CM, Ackerman KE, Berga SL, Kaplan JR, Mastorakos G, Misra M, et al. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017 102(5):1413–39. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00131

[5] Ackerman K, Cano S, De Nardo M et al. Fractures in relation to menstrual status and bone parameters in young athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015; 47 (8): 1577–1586. https://doi.org /10 .1249 /MSS .0000000000000574

[6] Keay N, Fogelman I, Blake G Bone mineral density in professional female dancers. British Journal of Sports Medicine 1997;31:143-147.

[7] Oosthuyse, T., Strauss, J.A. & Hackney, A.C. Understanding the female athlete: molecular mechanisms underpinning menstrual phase differences in exercise metabolism. Eur J Appl Physiol 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-022-05090-3

[8] Fehring RJ, Schneider M, Raviele K. Variability in the phases of the menstrual cycle. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006 ;35(3):376-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00051.x. PMID: 16700687.

[9] McNulty KL, Elliott-Sale KJ, Dolan E et al. The effects of menstrual cycle phase on exercise performance in eumenorrheic women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020; 50: 1813–1827.

[10] Keay N, Francis G Infographic. Energy availability: concept, control and consequences in relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53:1310-1311.

[11] Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the female athlete triad–relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med (2014) 48(7):491–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502

[12] Keay N, Rankin A Infographic. Relative energy deficiency in sport: an infographic guide British Journal of Sports Medicine 2019;53:1307-1309.

[13] Stellingwerff T, Heikura IA, Meeusen R et al. Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Med 2021 51, 2251–2280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01491-0

[14] Keay N, Overseas A, Francis G Indicators and correlates of low energy availability in male and female dancers BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2020;6:e000906. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000906

[15] Gifford R, O’Leary T, Wardle S etc al. Reproductive and metabolic adaptation to multistressor training in women Endocrinology and Metabolism 2021; 321; 2 https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00019.2021

[16] Prior, J. C. Adaptive, reversible, hypothalamic reproductive suppression: More than functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022 Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.893889

[17] Exercise and the Hypothalamus: Ovulatory Adaptations. Prior J. Endocrinology of Physical Activity and Sport 2020. Hackney A., Constantini N. (eds) Contemporary Endocrinology. Humana, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33376-8_8

[18] Keay N, Lanfear M, Francis G. Clinical application of monitoring indicators of female dancer health, including application of artificial intelligence in female hormone networks. Internal Journal of Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, 2022; 5:24. DOI: 10.28933/ijsmr-2022-04-2205

[19] Keay N, Craghill E, Francis G Female Football Specific Energy Availability Questionnaire and Menstrual Cycle Hormone Monitoring. Sports Injr Med 2022; 6: 177. DOI: 10.29011/2576-9596.100177

[20] Bedford J, Prior J, Hitchcock C et al Detecting evidence of luteal activity by least-squares quantitative basal temperature analysis against urinary progesterone metabolites and the effect of wake-time variability European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 146 (2009) 76–80

[21] McCarthy O, Pitt J, Keay N et al Passing on the exercise baton: What can endocrine patients learn from elite athletes? Clinical Endocrinology 2022: 96(6): 781-792 https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.14683

[22] Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen JK, Burke LM, et al IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency : 2018 update British Journal of Sports Medicine 2018;52:687-697.

[23] National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS). Accessed February 2022. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/amenorrhoea/management/secondary-amenorrhoea/#managing-osteoporosis-risk

[24] Labrie F, Martel C, Bélanger A, Pelletier G. Androgens in women are essentially made from DHEA in each peripheral tissue according to intracrinology. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;168:9-18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.12.007. Epub 2017 Jan 30. PMID: 28153489.

[25] Eklund E, Berglund B, Labrie F, Carlström K, Ekström L, Hirschberg AL Serum androgen profile and physical performance in women Olympic athletes Br J Sports Med 2017; 51(7):1301–1308

[26] Berin E, Hammar M, Lindblom H et al. Resistance training for hot flushes in postmenopausal women: A randomised controlled trial. Maturitas. 2019;126:55-60. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.05.005. Epub 2019 May 14. PMID: 31239119.

[27] Bermingham K, Linenberg I, Hall W et al. Menopause is associated with postprandial metabolism, metabolic health and lifestyle: the ZOE PREDICT study. Preprint Lancet. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn .com /abstract 4051462; http://dx .doi .org /10 .2139 /ssrn4051462

[28] Mandrup C, Roland C, Egelund Jon et al. Effects of high-intensity exercise training on adipose tissue mass, glucose uptake and protein content in pre- and post-menopausal women. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. 2020; (2): 60. https://www .frontiersin .org /article /10 .3389 /fspor .2020 .00060 DOI 10.3389/fspor.2020.00060

[29] Watson S, Weeks B, Weis L et al. High-intensity resistance and impact training improves bone mineral density and physical function in postmenopausal women with osteopenia and osteoporosis: the LIFTMOR randomized controlled trial. JBMR. 2018; 33 (2): 211–220. https://doi .org /10 .1002 /jbmr .3284

[30] Rymer J, Brian K, Regan L. HRT and breast cancer risk. Editorial BMJ. 2019; 367: l5928. https://doi .org /10 .1136 /bmj .l5928

[31] Management of Menopause. Sixth Edition. British Menopause Society 2017