Personal Energy Availability Questionnaire (PEAQ)

If you are striving to reach your peak performance, then the PEAQ can help you reach your personal full potential. Click here to get started on the PEAQ

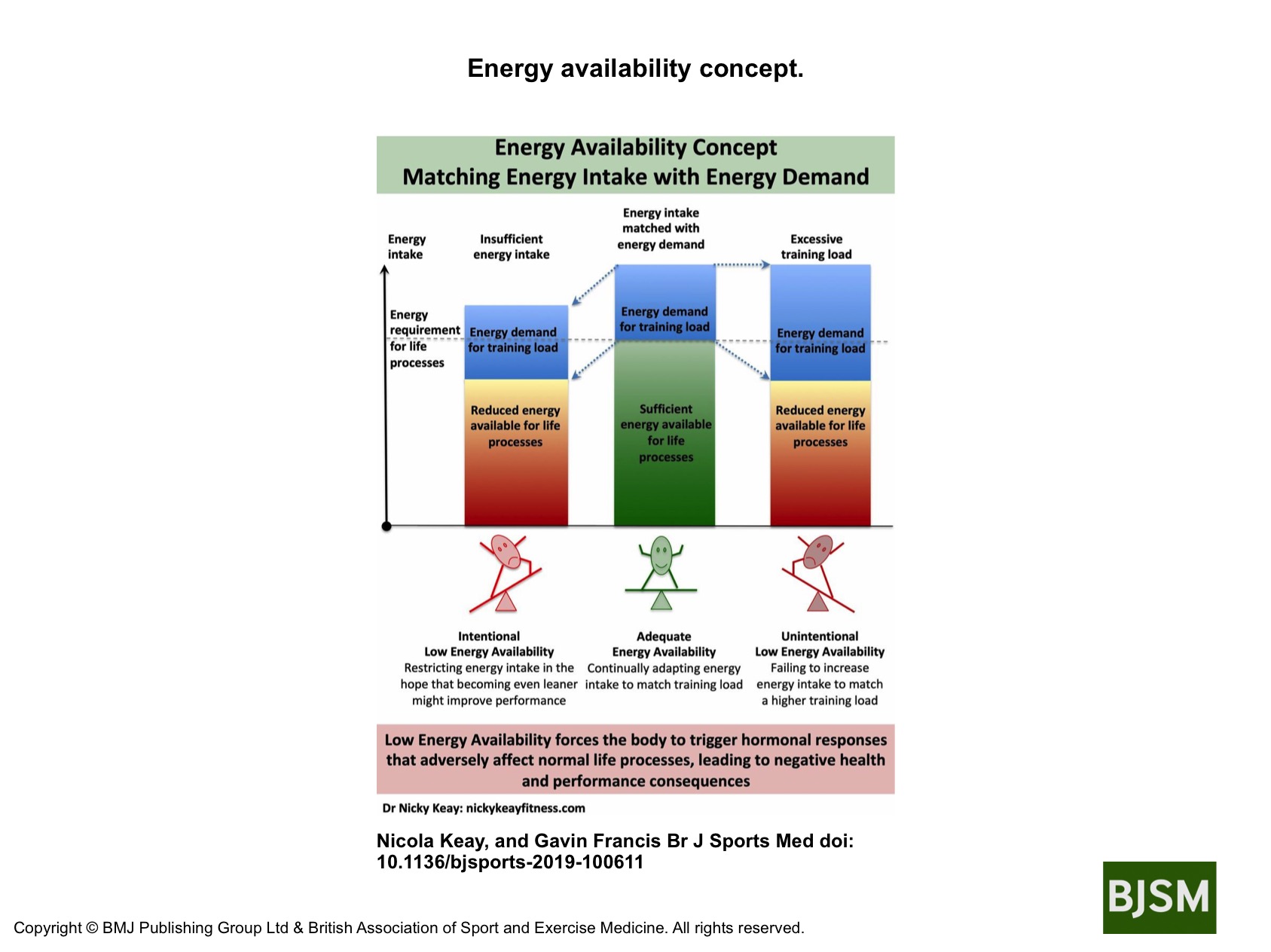

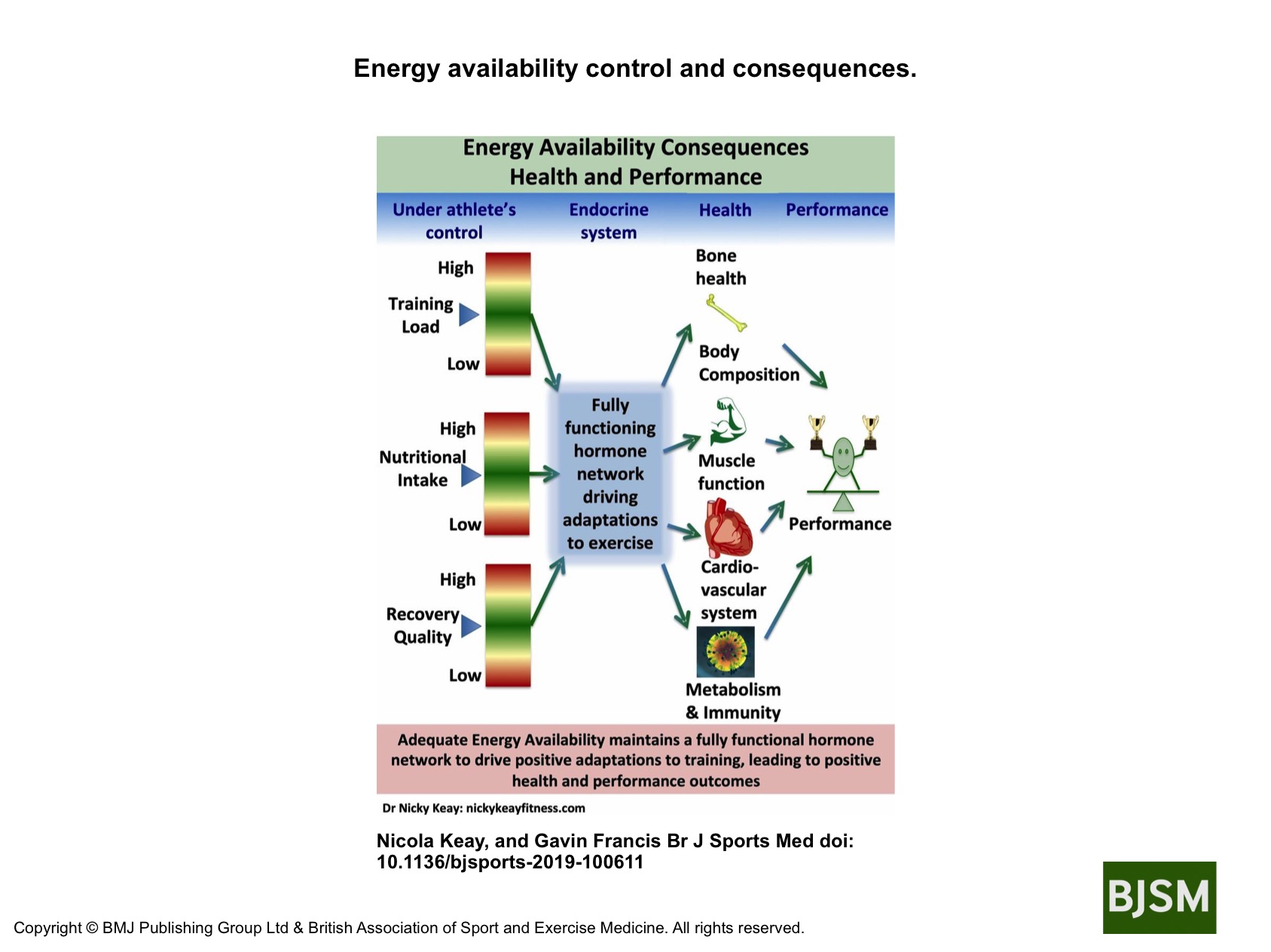

Matching your energy intake to your energy demands helps you reach your personal peak health and exercise performance. On the other hand, failing to meet your energy demands results in low energy availability. This increases your risk of developing relative energy deficiency (REDs) and its adverse health and performance consequences.

People of any age, whatever their level and type of exercise, can be at risk of developing REDs; from elite dancers and athletes to recreational exercisers.

The PEAQ is a mobile Application that will guide you through a series of questions about exercise, physical characteristics, nutrition, hormone function and well-being. It just takes a few minutes.

Your PEAQ report instantly generates a REDs Risk Score and provides valuable insights into your energy status and potential risks, along with guidance. The PEAQ is intended for those 16 years of age and over.

The PEAQ has been developed based on in several published research studies where the questionnaire responses and scores have been correlated with measurements of hormones and bone health in athletes in various sports [1-7] and dancers [8-12]. These questionnaires were cited in the updated International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement on REDs 2013.

However the PEAQ it is not a substitute for seeking medical advice. Dr Nicky Keay offers personalised health advisory appointments

Get started on your journey to reach peak performance by completing the PEAQ.

References

- Keay, Francis, Hind Low energy availability assessed by a sport-specific questionnaire and clinical interview indicative of bone health, endocrine profile and cycling performance in competitive male cyclists BMJ Open Sports and Exercise Medicine 2018

- Keay, Francis, Hind Clinical evaluation of education relating to nutrition and skeletal loading in competitive male road cyclists at risk of relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S): 6-month randomised controlled trial BMJ Open Sports and Exercise Medicine 2019

- Keay, Francis, Hind Bone health risk assessment in a clinical setting: an evaluation of a new screening tool for active populations MOJSports Medicine 2022;5(3):84-88. doi: 10.15406/mojsm.2022.05.00125

- Assessment of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, Malnutrition Prevalence in Female Endurance Runners by Energy Availability Questionnaire, Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis and Relationship with Ovulation status. Clinical Nutrition Open Science 2025S.

- Body composition, malnutrition, and ovulation status as RED-S risk assessors in female endurance athletes, Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2023, 58 :720-721

- Keay N, Craghill E, Francis G Female Football Specific Energy Availability Questionnaire and Menstrual Cycle Hormone Monitoring. Sports Injr Med 2022; 6: 177

- Keay N. Current views on relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs). Focus Issue 6: Eating disorders. Cutting Edge Psychiatry in Practice CEPiP. 2024.1.98-102

- Keay N, Francis G, AusDancersOverseas Indicators and correlates of low energy availability in male and female dancers. BMJ Open in Sports and Exercise Medicine 2020

- Nicolas J, Grafenuer S. Investigating pre-professional dancer health status and preventative health knowledge Front. Nutr. Sec. Sport and Exercise Nutrition. 2023 (10)

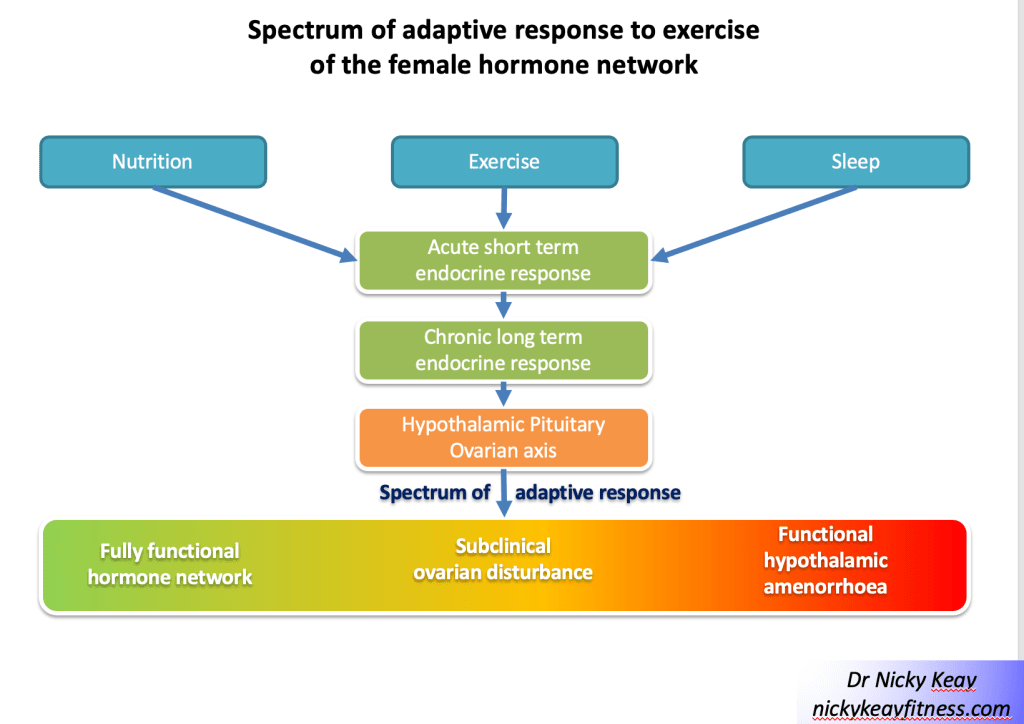

- Keay N, Francis G. Longitudinal investigation of the range of adaptive responses of the female hormone network in pre- professional dancers in training March 2025 ResearchGate DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.30046.34880

- Nicola Keay, Martin Lanfear, Gavin Francis. Clinical application of monitoring indicators of female dancer health, including application of artificial intelligence in female hormone networks. Internal Journal of Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, 2022; 5:24.

- Nicola Keay, Martin Lanfear, Gavin Francis. Clinical application of interactive monitoring of indicators of health in professional dancers J Forensic Biomech, 2022, 12 (5) No:1000380

- Mountjoy M, Ackerman KE, Bailey DM et al 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57:1073-1098

- Keay N “Hormones, Health and Human Potential: A guide to understanding your hormones to optimise your health and performance” Sequoia books 2022

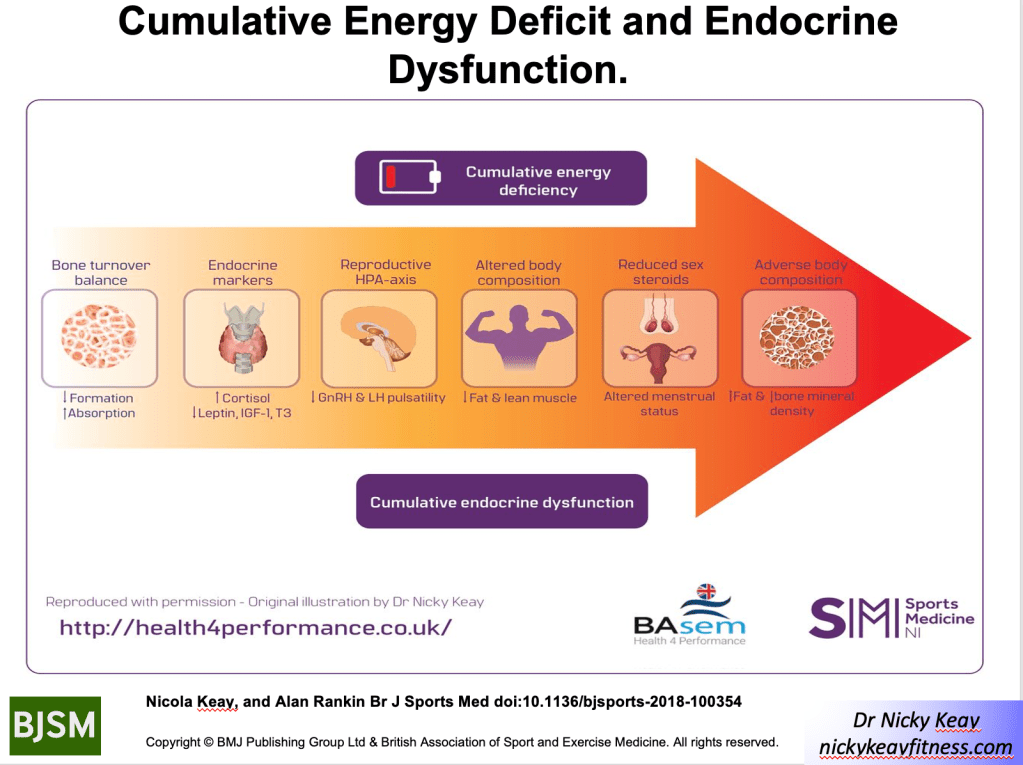

To recap, RED-S is a situation of low energy availability (LEA), which can lead to adverse health and performance consequences[3,4]. LEA can be a result of intentional energy restriction, which covers a spectrum of issues with eating from disordered eating to full blown clinical eating disorder. Ironically the original intention of these eating issues may have been to improve athletic performance, yet

To recap, RED-S is a situation of low energy availability (LEA), which can lead to adverse health and performance consequences[3,4]. LEA can be a result of intentional energy restriction, which covers a spectrum of issues with eating from disordered eating to full blown clinical eating disorder. Ironically the original intention of these eating issues may have been to improve athletic performance, yet